Last month, the Texas House Appropriations Committee gathered to hear state budget requests from agency heads. Rising costs and the impacts of inflation took center stage as pension stakeholders and retirees, for example, reported on how rising inflation is eroding their pension benefits.

With the challenge of inflation likely to continue to be at the forefront of all of the state’s major financial discussions when the Texas legislature reconvenes in January 2023, it is essential to understand how the state government determines the health of its public pension funds and how policymakers can protect public retirees from the degradation effects of inflation.

How Texas defines “actuarially sound”

In the Sept. 8 hearing, members of the Texas House Appropriations Committee explored the importance of being “actuarially sound” in response to the numerous calls by lawmakers and retired educators to follow up on 2019’s 13th check by issuing more inflation relief to provide cost-of-living adjustments to retirees during the next legislative session.

Rep. Carl Sherman (D-Desoto) asked Teachers Retirement System of Texas (TRS) Executive Director Brian Guthrie about the health of the state’s largest public pension plan. In posing his question, Rep. Sherman focused on the term “actuarially sound” specifically. Guthrie noted that Texas currently defines “actuarially sound” as taking less than 31 years to amortize, or fully fund, every pension dollar earned by members of the pension plan. That definition is set in statute and applies to all the state’s major public pension systems. You can watch Guthrie’s full response on being actuarially sound and the timeline for paying off the state’s unfunded liabilities below.

What does a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for retirees have to do with a technical definition?

This technical issue is on the minds of retirees because the Teacher Retirement System (TRS) of Texas and the legislature can only issue a cost-of-living adjustment or a 13th check if the pension fund is determined to be “actuarially sound.” As Guthrie noted, this is currently defined as the pension fund’s amortization period not exceeding 31 years.

With this year’s high inflation rates hitting retirees living on fixed incomes the hardest, it is not surprising that retiree groups and their allies are advocating for a cost-of-living adjustment in the next legislative session. But just as was the case in 2019, when the state legislature opted to issue a 13th check to make up for the past decade’s inflation instead of adding liabilities to the fund, giving a permanent cost-of-living benefit increase next session would attach future obligations to the state and taxpayer in perpetuity. These obligations should be fully prepaid to limit their impact on the long-term financial health of the pension system. If state policymakers want to address the issue once and for all, they should look at launching a new TRS tier for new hires that includes a predictable cost-of-living adjustment as a core benefit in retirement.

Did TRS suggest the state’s definition of “actuarially sound” is outdated?

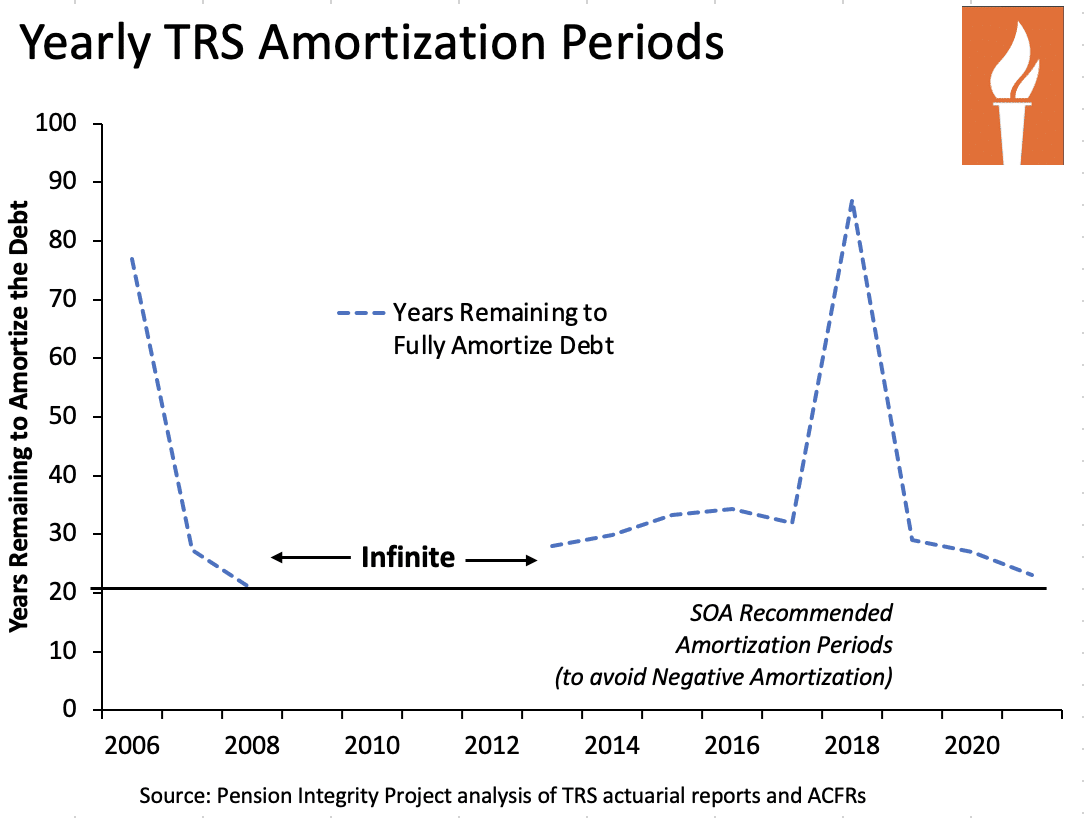

To be “actuarially sound” is less of a universal definition or number than a collection of policies reflecting short and intermediate timeframes. Policymakers would do well to listen to Teacher Retirement System’s Guthrie and talk to other actuaries and the Texas Pension Review Board about a more contemporary idea of how the state should judge the financial stability of its public pension systems. For example, Guthrie notes that other groups, including the Society of Actuaries, recommend public pension amortization periods be no longer than 15-to-20 years. Setting an amortization period and allowing rates to adjust—the policy the Employees Retirement Plan (ERS) recently adopted—is also more actuarially sound than the current TRS policy of setting rates and allowing amortization periods to adjust.

Teacher Retirement System actuaries have now built the increased contributions from 2019’s pension reform, Senate Bill 12, into the plan’s funding valuation. The effect was a shorter amortization period calculation, from 87 years to 29 years, if TRS manages to do something it’s never done: meet all of its actuarial predictions, like investment returns and mortality rate, 100% accurately.

After the market turmoil in 2020 and then record-breaking investment returns in 2021, TRS actuaries are now reporting a 26-year calculation, which is about where the system stood in 2013. The impact of the 2022 investment year, likely well below the pension system’s long-term expectations, has yet to be reported. But the low-to-negative investment returns expected are bound to bring that amortization figure closer to, if not beyond, the 31-year mark.

If retirees and budget managers want predictable inflation relief that protects the value of pension benefits in a financially prudent manner, updating the state’s definition of “actuarially sound” to align with the Society of Actuaries’ recommendations would be a good first step.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.