The National Institute on Retirement Security recently published research claiming a “retirement efficiency gap” between traditional defined benefit public pension plans and alternative defined contribution retirement plans. The National Institute on Retirement Security analysis compares the costs of typical defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans, finding that defined benefit pensions can provide the same retirement benefits for lower total contributions. While the report makes some valuable observations, the analysis misses key facts and wrongly suggests that defined benefit plans have superior efficiency.

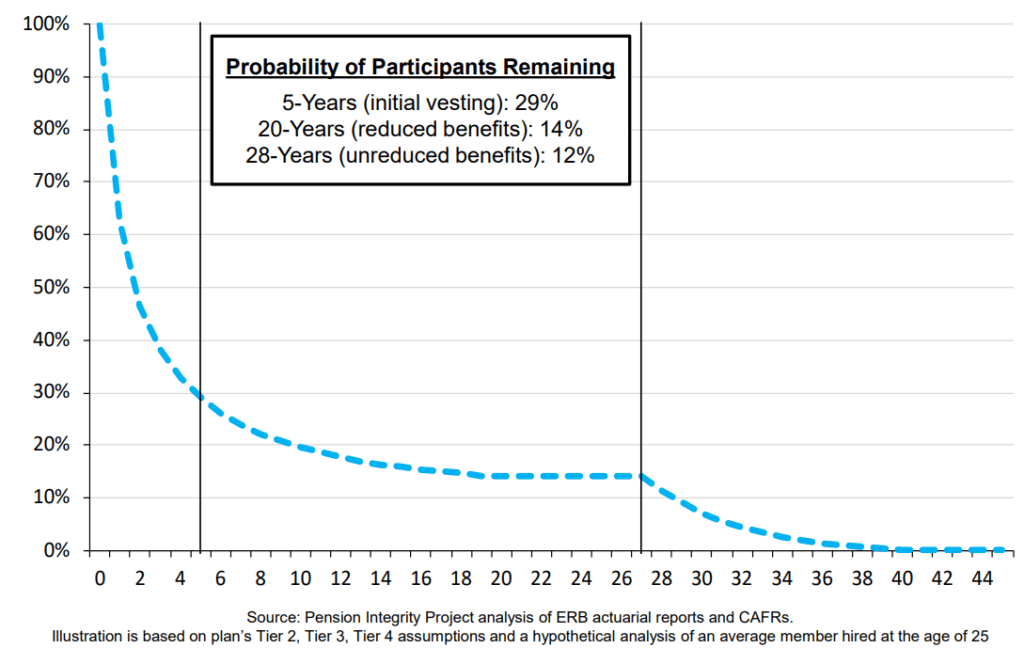

A key issue with the National Institute on Retirement Security’s (NIRS) analysis is that it does not address a more overarching question about how the pension benefits of these plans are distributed. It has been well documented that most workers hired by the government do not stay in public employment long enough to receive a maximized pension. In Reason Foundation’s analysis of New Mexico’s Educational Retirement Board (ERB), the pension plan for teachers, only about 12% of newly hired employees make it to full retirement. This statistic means that the vast majority of workers in ERB are not reaping the full benefits of a defined benefit pension plan. The distribution of benefits among public workers in different plan designs (e.g., DC, DB, hybrid, etc.) is just as important, if not more important, than the cost efficiency argument. This article will primarily focus on the cost efficiency argument discussed in the NIRS report, and we will expand the conversation in a follow-up article later detailing the distribution of benefits between DC versus DB plans.

Active Managers versus Individual Investors

In its analysis, NIRS argues that because pension funds are managed by sophisticated fund investors, they are able to generate higher investment returns and avoid unnecessary fees due to their larger scale relative to an individual investor. Because defined benefit plans have pooled expenses, the argument goes, that these plans have economies of scale advantage and thereby lower management fees.

The argument about advantages in managing the risk of runaway costs fails to hold up when examining outcomes of the last few decades. Institutional investors have struggled with managing this risk, leading to severe underfunding of pension plans across the country totaling roughly $650 billion, a sum that will likely increase again this year. This questions the very foundation of NIRS’ assertion that active institutional investors can manage risk better. Many pension systems clearly have not managed risk very well for many years, suggesting that hypothetical analyses should be taken with a grain of salt when they overlook the real world of existing unfunded liabilities.

Regarding fees, NIRS bases their assumptions on a 2007 Center for American Progress Study arguing that hidden fees in 401(k) plans devalue total pension wealth by 20-30%. The fee differences outlined in the CAP study are the fee differences between retail and institutional shares for investing. Under this argument, DC plans only have access to retail shares and DB plans have access to institutional shares and thereby lower fees.

Yet this argument does not reflect reality. DC plans (public or private) that are larger in size, such as Utah’s DC retirement system (URS), have access to institutional shares just like other DB plans, and therefore do not suffer the economies of scale problem when it comes to fees. The real comparison here should be between retirement plans of different sizes rather than the type of retirement plan design.

It is true that there are people in some DC plans that have likely seen unnecessarily high fees, but that is also happening with pensions overall. There have been several reports in recent years pointing out how some public pension plans have seen excessive fees. Ohio’s State Teachers Retirement System, for example, reported paying $175 Million in fees to investment managers.

In terms of advantages in overall investment results between active managers versus individual investors, recent history suggests otherwise. A study conducted by SPIVA found that active funds over the last decade have either underperformed or been on par with traditional index funds that passive investors use. The reasons vary, but in general, active investing has not had a clear advantage in returns.

This conclusion even holds when examining alternative investments like private equity, which has increased in prominence among pension funds seeking higher returns going from 3.6% allocation in 2001 to 9.2% by 2019. A recent study by Reason examined the performance of private equity versus the S&P 500 over the last decade, finding that after adjusting for fees, private equity actually achieved results lower than the index.

Balanced Portfolio

NIRS also makes the argument that active institutional investors can manage market risk better with a more balanced portfolio. NIRS’ claim is not that the typical novice investor will create a risky DC portfolio, but rather they will choose lower return instruments such as bonds at the latter part of employment and in post-employment. This is a fair observation, as individual passive options like target-date funds adjust their investment strategies to reduce risks as they get closer to retirement. They argue that because of the lower returns, the DC plans will need to contribute more to the plan in order to generate the same benefit. According to NIRS’ calculations, the average contributions would need to be double (16% versus 32%) in a traditional DC plan than they would need to be in a DB plan to yield the same retirement savings.

NIRS models hypothetical DC versus DB portfolios to compare returns over a person’s lifetime. The modeled asset allocation of the DC plan changes over time, while the DB’s allocation remains uniform throughout. They also split the DC plan into a regular DC plan and an “ideal” category based on similar efficiencies to a DB plan. The results show that at age 30—where the fixed income allocation is lowest—the DB return is around 6.7%. Meanwhile, the “ideal” DC return is slightly higher around 7%, with the regular DC return slightly higher than that at around 6.6%. At age 96—the final year for their model—the DB return holds because the asset allocation is the same, while the “ideal” DC and regular DC returns drop by 2.3% and 4% respectively.

There are a couple of problems with this analysis. First, while they may lack the sophistication of pension insiders, individual investors do have access to direct tools and financial planners to better help with asset allocation, and well-designed public DC plans require the third-party administrator to offer some form of advice and counseling to participants. Institutional DB plans are not the only plans that have access to advisors or other tools to help with investing.

Based on Vanguard’s lifepath fund for different age groups, the typical individual under 40 has an allocation for equities of around 90%. NIRS uses a 7% return for equities to benchmark, which is surprising since the average S&P 500 growth rate over the last 10 years was 12% according to SPIVA. With a 90% allocation toward equities, you would expect their return for that age group to be much higher than 6.8%. This warrants a closer examination of the assumptions used in the NIRS analysis.

In terms of a balanced portfolio, real-world results do not support that DB plans are more risk-balanced through professional management than when managed by an individual in a DC plan. DB plans have been slow to lower their long-term investment return assumptions, which has created challenges for fund managers. Finding it more difficult to generate returns to match these increasingly unrealistic assumptions, many plans have assumed greater and greater risk in recent years, expanding shares in alternative investments like private equity and hedge funds thereby exposing portfolios to more volatility and risk.

Risk Pooling Between Retirees

NIRS makes the case that DB plans inherently have advantages in risk pooling among retirees. This insulates retirees from longevity risks—the risk that a person lives longer than their retirement benefits. NIRS argues that, in a DC plan, if a person has budgeted to save enough for retirement expecting to live to a certain age but ends up living longer, they are in trouble. In addition, if they live fewer years than expected and have surplus retirement savings, that excess is “wasted.” According to NIRS, about one in six dollars saved for a DC retirement plan does not go toward retirement. The NIRS argument obscures some critical points that undermine their overall position.

When NIRS talks about the risk pooling between retirees in a DB, where the money comes from for longer longevity scenarios remains undiscussed. NIRS brings addresses this element when discussing DC plans (arguing that the workers have to figure out how to budget for how long they anticipate living). But in a DB plan, if benefits are projected for an assumed number of years and the actual experience ends up exceeding those assumptions, then the money will generally come from the government employer (or future taxpayers) via higher contributions. If NIRS views a retiree experiencing an excess of funds as an inefficiency, they should also recognize real-life unexpected costs commonly differ from the cost assumptions of DB plans. This also raises the question as to who is supposed to benefit from fund excesses. If the individual’s (or DC plan’s) excess funds are deemed inefficient compared to a pool of members in a DB plan, are not excess funds in a DB plan also inefficient to the individual? Recognizing only one side of excess funds is likely leading to an unbalanced conclusion.

The NIRS study correctly identifies longevity risks associated with the traditional DC plan, but the risk of outliving one’s benefits can be eliminated entirely with the purchase of annuities such as what is offered by TIAA or in the UK with their Collective DC. More and more government employers are building these annuities into the DC products they offer. Essentially, an annuity option eliminates both “wasted” money and the insufficient fund issues NIRS raises. In fact, an annuity from a DC plan is actually more likely to serve an individual public worker when compared to a DB plan, seeing as DC plans vest immediately and many workers hired into government positions leave employment before the pension vesting period concludes, forfeiting the employer contributions made on their behalf.

NIRS Analysis Benefit Efficiency

This argument was not part of NIRS’s study but is crucial to address. Cost efficiency is just one lens through which to view a comparative retirement design, but there are others that are equally important. Even if a DB plan is more cost-efficient than a DC plan, what good is that if the worker doesn’t even stay until full retirement to collect the benefits in their intended entirety?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the average worker changes jobs around 12 times during their career. The average tenure of someone at a job is typically between four to five years. This means that many workers are not staying long enough to receive a pension. In some cases, they are not even staying long enough to be vested in the pension system itself. In the example of New Mexico ERB, cited earlier, only about 12% of New Mexico teachers make it to full retirement and fewer than 30% of them even make it to the vesting period. This means that even if a DB plan is more efficient, it is only going to a fraction of the workers, suggesting that it is inefficient from a benefit access perspective.

Probability of Members Remaining in New Mexico ERB

In NIRS’ own study, they assume that the 1,000 workers used for their analysis all make it to full retirement with no turnover, death, or deferred benefits. NIRS does make an assumption about career breaks for parenting but still assumes no turnover or other disturbances. This is obviously not a realistic scenario.

A more comprehensive perspective on the strengths and weaknesses of the two plan types would include a wide examination of different situations that are common for employees and the rates at which these situations occur. The concept of benefit efficiency, which is the idea of how widespread benefits are distributed in DC versus DB plans, will be fleshed out more in a follow-up piece. But for the sake of this explanation, whatever cost-efficiency NIRS has argued for in traditional DB pension plans comes at the expense of limiting access to the benefit for a very constrained population.

The “Efficiency Gap”

Putting all of the above together, NIRS makes a savings breakdown of DC versus DB plans in terms of cost and efficiency. NIRS notes the difference between an “ideal” DC versus a regular DC plan in that an “ideal” DC plan has the same fee structure as a DB plan. While this has been disputed in the points above, it is worth looking at the analysis’s final number of close to a 50% savings between a DB versus DC plan. While it is not possible to dispute the exact percentage, since the efficiency calculation is not provided, the idea that a DC plan is twice as expensive as a DB plan does not pass the basic litmus test.

If DB plans were really more efficient than a DC plan to that degree, why have the companies that abandoned them in the 1980s and 1990s not gone back and adopted new DB pension plans, having learned the cost efficiency lesson of DC plans firsthand? Companies today are always trying to cut costs. Thus, a more efficient retirement system would likely be appealing to them. The fact that most private companies have chosen and remained in individualized retirement structures—in contrast to pensions—suggests an efficiency gap as large as NIRS has estimated is likely overstated.

Conclusion

There are clearly issues with both DC and DB plans that need to be worked out during plan design to ensure success, such as benefit structure, investment management, and funding policies. NIRS is right to focus on the importance of these issues but has relied on too narrow of a perspective, overlooking several key considerations that extend beyond just costs to the employer.

NIRS assumes a near-perfect scenario for DB plans when assessing their viability – no change in workforce numbers, no underperformance in investment returns, and no unexpected fees. This scenario has not been the lived reality for most pension plans.

In order to fully understand the strengths and weaknesses of each plan type, one must examine all aspects involved in the saving and distribution of retirement benefits, including careful consideration of plan recipients. The ultimate goal of a truly efficient retirement plan is to have as many workers as possible receive adequate benefits to provide for a healthy life after employment. Cost efficiency, while an important factor, is not a complete view of what a retirement plan is and what it is meant to achieve.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.