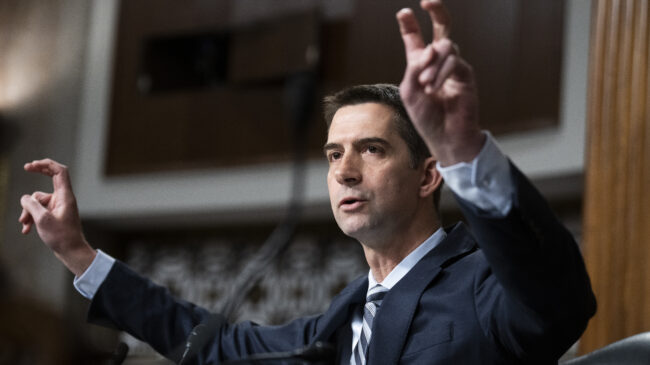

Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) were among the bipartisan cosponsors of the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act (PCOA), a bill that proponents claim would limit the power of so-called big tech companies. The legislation would set a strict standard for mergers and acquisitions, drastically increasing the workload for companies and the agencies which oversee these transactions and potentially limiting the capacity for economic growth.

Typically, an organization looking to purchase an outside company may either create an entirely new entity by buying another firm, called a “merger,” or obtain the smaller company and absorb it in an “acquisition.” There are two main types of mergers. First, a firm can execute a “killer” acquisition whereby another firm is acquired and immediately terminated. Another style is called a “nascent ” acquisition, where a large company purchases a smaller one because it desires the firm’s technology or employees.

Companies looking to combine must apply to the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice to prove that a transaction will not decrease market competition. Most of these applications are successful on their first review. Only 2% of applications require additional scrutiny from regulators, called “second requests,” during which the company must prove that the deal will not harm market competition. These requests can be incredibly laborious for companies to comply with. Providing all documents can take an organization over 10 months, and a company may have to provide information like organization charts, product specifications, and employee testimony. One “model” second request asks a company to provide 112 different types of evidence, each of which must be uniquely formatted and organized.

The PCOA seeks to prevent tech companies from buying smaller companies. It would also significantly increase the current steps and standards for tech companies involved in mergers and acquisitions, lifting evidence requirements so unnecessarily and harshly that it would dramatically raise compliance and litigation costs, potentially stymying tech innovation, without helping taxpayers or consumers.

The PCOA aims at technology-related transactions worth more than $50 million dollars so it can target major technology firms such as Amazon, Apple, Facebook (Meta), and Google. However, analysis of previous Federal Trade Commission data shows some of the bill’s flaws.

For example, Twitter acquired messaging company Quill in 2021. Twitter shut Quill down and absorbed its team, with Twitter’s direct manager for core technology tweeting that the company would integrate Quill’s technology into its direct messaging system. Although this scenario seems precisely like the type of transaction the PCOA would like to monitor or block, it would go unreported under the PCOA because Twitter bought Quill for $16 million, far below PCOA’s $50 million threshold.

Meanwhile, the PCOA would apply its strict terms to deals above the $50 million threshold, even if it seems clear that the deal wouldn’t affect market competitiveness. For example, deals like Zoom buying the customer service tech firm Five9 to help it branch out into other markets would needlessly be put under regulators’ microscopes. Similarly, Apple purchasing PA Semi, which increased semiconductor competition by helping Apple create its own chips, would be subject to intense federal scrutiny—even though these types of moves improve the market.

Passing the PCOA would also burden the government agencies that review mergers and acquisitions. The bill would require the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice to verify information that applicants submit, meaning that an increased applicant workload for tech companies would translate into increased regulator workloads.

The FTC has previously discussed how increasing investigation requirements hinder its ability to review transactions efficiently, noting that the expansion of information certification requirements, which began in the 1990s, continues to strain the organization. As the FTC emphasized in a report, “an unintended collateral effect [of increasingly complicated merger analysis] has been to increase the burden on the parties and the agencies.”

Stress on the FTC’s merger analysis employees has only continued to grow since then. The commission’s funding and staff have decreased yearly for the past 12 years. In 2021, the FTC had to modify its review process because it was so far behind in investigating applications. It is unlikely that the FTC could effectively handle the additional verification associated with reviewing applications under a PCOA-style system.

PCOA would create strict standards for technology mergers and acquisitions that research suggests would burden both technology companies and regulatory agencies. The bill aims to limit big tech’s power, but it would actually end up limiting innovation, start-up companies, and economic growth.