Quality child care is unaffordable for many parents in the United States and barely affordable for many more. The average cost of center-based child care is over $12,000 a year. Daycare centers, however, aren’t getting rich, and they are usually non-profits or small businesses with razor-thin profit margins. Child care workers’ pay, on average, is low enough to fuel increasing controversy in its own right. Providers are regulated to the hilt, which increases costs and strains daycare centers, families, and workers alike.

We might expect to find one or more interest groups guarding economic and political power while everyone else in the industry is squeezed, but child care has no clear suspects. Unlike big tech or big pharma, there is no group of ‘big child care’ companies setting high prices or leveraging the power to get government regulation to stifle small startups because there’s not enough money in it. There is no workers’ union resisting change. While current regulation is overly complicated, costly, and burdensome, there is no bureaucracy whose power and jobs stem from the status quo.

The White House made child care a marquee item in its Build Back Better plan at a projected cost of over $200 billion. President Joe Biden’s proposal focuses primarily on subsidizing existing licensed child care options for low- and middle-income households and subsidizing providers in areas where supply is too low.

Debates over big-ticket plans like the Build Back Better proposal often force us into familiar political tribes, crowding out fresh thinking and innovative ideas on a small scale. However, a more detailed look at the many tradeoffs young parents face and the many arrangements they make to care for their young children shows how critical informal arrangements are and how daycare is the right option only for some people some of the time. By engaging local communities and research across multiple fields, there is scope to facilitate more access to this informal sector that should interest both sides of the Build Back Better debate.

Parents prioritize the basic care of young children above virtually anything else. Maintaining a safe, positive, well-monitored environment around the clock for infants and toddlers, and to a lesser, but still significant, degree, for older children is not a matter of if, but how. We often bundle this necessity in our definition of child care with other vital services such as early-childhood education, but the distinction is important. What many call America’s child care crisis is not a crisis of children not receiving essential care but rather what must be sacrificed to provide it.

Care, especially for the youngest children, must be provided 24 hours per day by one or both parents at home, or children need to be sent to daycare or placed in the care of others—often family members, close friends, and neighbors. The latter category is often called the informal sector of childcare, which is a part of the problem often lost in policy debates, but just as prominent for all parents as daycare.

When they are fortunate enough to have the suitable options, parents often choose “informal” care over a daycare center. An illustrative example is Sen. Elizabeth Warren, herself the author of a childcare plan for her 2020 presidential campaign that was similar to the Build Back Better plan being pushed by the Biden administration.

Before detailing her plan, Sen. Warren told a personal story of struggling to find adequate and affordable care for her young children while starting as a law professor. At her wits’ end, she called her aunt, unsure of what to do. Warren says:

Then Aunt Bee said eleven words that changed my life forever: “I can’t get there tomorrow, but I can come on Thursday.” Two days later, she arrived at the airport with seven suitcases and a Pekingese named Buddy — and stayed for 16 years.

Warren’s dilemma is one to which many young parents likely relate, whether starting promising careers or simply needing work to make ends meet. And while Warren may have been unusually lucky, the importance of one’s close social ties—family and friends—in caring for children while balancing life’s other demands is quite common.

Ensuring basic care for children can cause not just parents but other close relatives and friends to reshuffle their major life decisions, further underscoring the paramount importance modern society places on caring for young children. Warren and those personally close to her were prosperous and stable enough to shift resources such that a young mother didn’t have to choose between her children’s well-being and her career.

Not everyone is so fortunate. Families and close friends in poorer communities put similar importance on helping young parents care for children, but the help provided either by a single family member or many people chipping in is more likely to entail sacrificing other near-essential activities. Missed days of work and lost opportunities for education and career development become more likely in groups where those sacrifices hurt the most, further entrenching people in poverty.

Close social bonds also often come with trust and intimacy between parent and caregiver that arm’s-length daycare centers cannot match. Familiar relationships allow richer assessments of quality and safety than rules written down by a center or its regulators. Parents often seek to mimic these relationships even in informal childcare arrangements where they don’t already know the person well. Live-in nannies effectively become part of a family, and parents are more likely to trust neighbors’ children to babysit at a younger age than a babysitter they do not know.

Center-based care and arrangements built on close personal ties are imperfect substitutes. Some informal arrangements, as well as parents staying home, have uniquely desirable attributes. While this fact alone does not preclude center-based care as a viable model, the competition daycare centers face from these many arrangements plays a part in explaining the strained business model center-based providers face.

Many other goods and services historically produced in the home are now mostly supplied in the market. But child care, especially basic care for young children, lacks significant economies of scale. Few services are more labor-intensive.

Whether one agrees with the caregiver-child ratios that states impose on child care centers, there are only so many one-year-olds who can be put in a room and effectively monitored without needing more help. There is also little scope for center-based providers to invest and differentiate themselves.

Over-regulation of licensed child care is one symptom of this “trust gap.” Without the understanding naturally found in close personal relationships, busy families need to be able to find information to help them verify the quality and safety of potential center-based providers. If federal and state governments didn’t create these rules by edict, market forces would likely induce providers to develop them in some form.

Such rules might better reflect what some parents want, especially when the rules are allowed to meaningfully vary across providers. But they would still be rules on a piece of paper, inevitably falling short of the level of comfort parents find in child care from people they know. High prices and low-profit margins at daycare centers are a difficult stalemate to break.

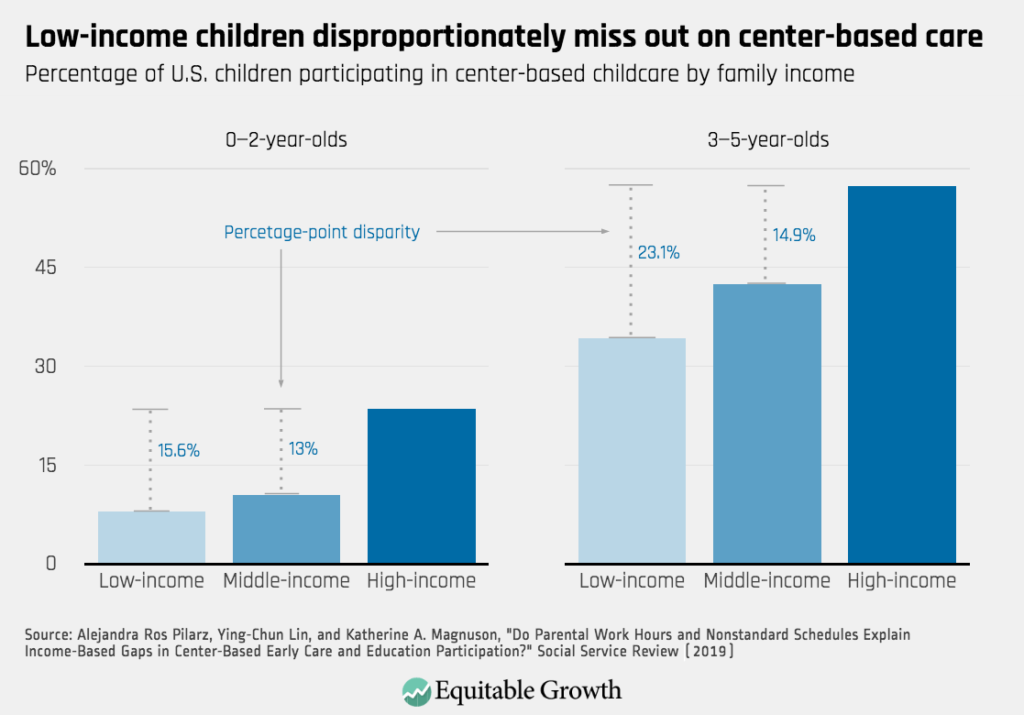

The graph below presents two critical insights:

Percentage of U.S. children participating in center-based child care by family income:

The original chart, reprinted from Equitable Growth, is titled, “Low-income children disproportionately miss out on center-based care.” This disparity is significant and almost certainly driven by high costs.

The chart’s high-income results are equally informative because high costs are not the only thing keeping Americans from putting their kids in daycare centers. Informal arrangements, big and small, appear to play a significant role in the childcare decisions of all parents.

Center-based child care sometimes fits some families’ needs, and affordability is but one of several factors limiting the viability of this model. The White House’s $225 billion plan in the Build Back Better proposal primarily focuses on helping parents pay for expensive center-based care. The subsidy fully covers daycare costs for low-income families and gradually phases out up to 2.5 times a state’s median income. The remaining child care money in the plan is mainly set aside for more subsidies–payments to providers to address supply issues in neighborhoods judged to be underserved.

Nowhere does the plan claim to realize cost savings, as “Medicare For All” proponents often promise. Nowhere does the plan promise to create higher quality child care than the often-useful but inherently limited center-based model. The only major change to the licensed center-based model that President Biden and Sen. Warren call for is higher pay and educational requirements for center workers, which is almost sure to increase costs for families and force some very qualified child care workers out of jobs.

Large federal spending on center-based and other licensed daycare will not solve the childcare crisis. Informal childcare is just as important to many parents and has some benefits that centers cannot replicate—which the data on income and center usage confirm.

The best way to facilitate relationship-based care in poor communities would be to ease people’s overall financial strain. Giving parents more-flexible help to find what works for them in the market or from family and personal connections will reliably lead to better outcomes than the government prescribing a few subsidized options.

As of this writing, the Biden administration is trying to keep its big-ticket child care plan on the table rather than getting the 2021 child tax credit, which expired, reinstated. The child tax credit was a help to low-income families, so rather than moving the child care policy in the right direction, the president’s plan is likely doubling down on the wrong one.

Searching for a magic-bullet national policy to strengthen informal care is tempting, but finding a way for a bureaucracy to avoid turning the unique benefits of personal relationships into costly top-down regulation is unlikely. In this case, national or state policy may not be the best way for civil society to contribute its resources and energy. But the informal sector is at least as large and important to parents as a daycare, and its results strain low-income parents disproportionately.

On a small scale, there are many promising ideas and the scope to implement and develop many more. For example, a southeast Detroit pilot program finds promising results from making educational, advisory, and problem-solving resources available to informal child care providers. The providers self-report that the biggest benefits stemmed from activities where they were put into groups and could interact informally rather than simply receiving instruction.

Another recent study shows opportunities to build social capital across informal networks of parents and providers and finds that single mothers plugged into these networks have an easier time returning to work than mothers using daycare centers.

The fundamentally bottom-up nature of this change, the very thing that makes it promising for new ideas bridging old partisan gaps, also creates big challenges in policy terms. Encouraging informal child care networks, advising non-profits on best practices and innovations, and presenting these informal networks as an often-desirable alternative to daycare is challenging in today’s political environment and difficult to scale at the state and national level.

While the significant taxpayer investments subsidizing both parents and providers of center-based care are an essential topic for public debate, the focus on the largest ticket items can distract policymakers and stakeholders from many important small ideas and improvements that could be made. And those policies will continue to be needed, whether some form of Biden’s Build Back Better plan passes or not.