As one of the top tourism destinations in the world, Florida is known for its warm, sunny summers marked by bustling theme parks and crowded beaches. In recent years, however, summer headlines have reported a growing number of blue-green algal blooms that could wreak havoc on the state’s tourism industry.

Blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, kill wildlife, poison pets, and have serious health consequences for humans. Algal blooms occur when large amounts of nutrients—originating from urban and agricultural areas—enter a body of water. Algae feed on the nutrients and grow until a slimy, green layer is formed on the water’s surface. The recent blooms originated predominately in Lake Okeechobee before spreading to the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries.

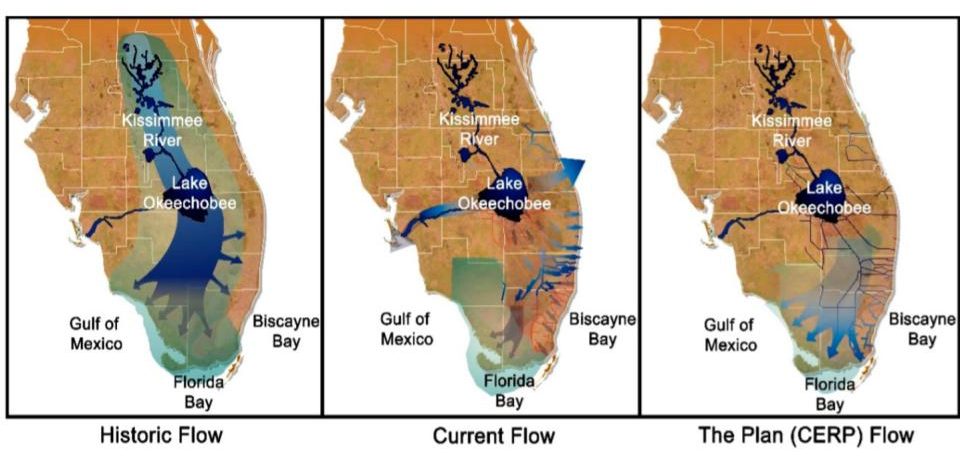

The spread of blooms to the coasts is the result of state and federal infrastructure projects which block the natural flow of water south to the Everglades and Florida Bay. Beginning in the 1850s, wetlands in the historic Everglades region were drained and cleared for human settlement. A series of devastating hurricanes and floods in the early 1900s prompted the construction of the Herbert Hoover Dike (HHD) surrounding Lake Okeechobee and a series of canals to the east and west to divert water through the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers when water levels in the lake climbed too high.

Today, over 2,200 miles of canals and 2,100 miles of levees controlled by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) regulate the flow of water in south Florida. While the HHD and other infrastructure projects provide flood protection to urban and agricultural communities in south Florida, they also alter the natural flow of water through the Everglades and contribute to the spread of algal blooms to coastal estuaries. There is wide agreement that more storage, treatment, and conveyance infrastructure in south Florida—especially surrounding Lake Okeechobee— is necessary but little progress has been made in the 20 years since the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan was authorized.

Among the most controversial pieces of the Everglades puzzle is the approximately 700,000 acres of agricultural land south of Lake Okeechobee (Lake 0). The area has been used for agriculture since the early 1900s and was formally designated as the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) in 1948. The primary crop grown in the EAA is sugarcane, accounting for nearly half the national supply of sugar.

Fertilizer runoff from agricultural areas is a major source of nutrient pollution that leads to algal blooms in Lake O. However, measures taken by producers and government authorities in the EAA to reduce nutrient pollution are highly effective at mitigating the impacts of agriculture in the area. In fact, a 2011 SFWMD report estimated that less than 10 percent of net phosphorus imports in the Okeechobee watershed originated from sugarcane production compared to 30 percent from urban areas and 60 percent from other agricultural activities mostly north of Lake O.

While sugarcane production in the EAA contributes a relatively small portion of the nutrient pollution in Lake O, agricultural lands in the area prevent more water from naturally flowing south. Environmental groups have long advocated for the state to purchase the agricultural land in the EAA and restore the natural flow of water from the lake.

In 2008, then Florida Gov. Charlie Christ planned to buy almost 200,000 acres of land from U.S. Sugar at a cost of $1.75 billion. After the recession, the deal was reduced to just 72,800 acres for $536 million before collapsing altogether in 2015.

Last month, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis announced a new deal to pay $1,940 per acre to terminate a 1,234-acre lease of state-owned land. The land will be used to construct the EAA Storage Reservoir—the single largest water storage and treatment project under the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan. Additional water storage in the EAA will allow more water to flow south thereby reducing the harmful freshwater discharges to the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers.

The buyout is expected to save the state about $16 million in construction costs by expediting the project timeline. Florida Crystals, the sugarcane producer occupying the land, enabled the deal by waiving a notice requirement which would have prevented the state from terminating the lease until at least three years after receiving a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

While the deal is significantly better for Florida taxpayers than previous attempts to purchase the land, buying out producers in the EAA may not be the best approach to addressing the challenges presented by the EAA in the future.

Instead, lawmakers could address the system of tariffs and subsidies that prop up the sugar industry and raise the price of land in the EAA in the first place. Federal policy effectively sets a minimum price for sugar in the US, typically well above the world market price. Moreover, the US government is required to buy excess sugar in times of surplus and resell it at a loss to ethanol producers. These backward policies cost consumers between $2.4 and $4 billion annually to the benefit of large sugar corporations. Even if sugar producers in the EAA are not the primary cause of nutrient pollution, they shouldn’t receive special treatment at the expense of taxpayers.

It is also critical that restoration efforts don’t inadvertently exacerbate the problem. Sending more water south is essential to addressing blooms in the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee estuaries but doing so may increase the risk of spreading blooms south. Additional storage and treatment infrastructure north of Lake O to clean water before it reaches the lake could reduce this risk.

Public-private partnerships that convert privately-owned land into massive artificial wetlands, or water farms, are one possible model. Existing water farms on former agricultural land north of Lake O have led to significant nutrient reductions and are more cost-effective than other storage and treatment projects. Increased use of water farms surrounding the lake could also achieve greater storage and reduce costs while preserving the rights of property owners.

Gov. DeSantis’ actions on Everglades restoration indicate a serious commitment to cleaning up Florida’s water, but decades of neglect mean there is still much to be done. The EAA reservoir is just one of over 50 projects under the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan authorized nearly 20 years ago. Massive infrastructure costs, dispersed blame, and bureaucratic red tape have largely stalled progress over that time.

Going forward, private investment, evidence-based decision making, and improved inter-governmental coordination will be key to avoiding past mistakes and achieving restoration goals in a timely manner. The future of our state depends on it.