This commentary was submitted as public comment to the Montana Interim State Administration and Veterans’ Affairs Committee during their consideration of HJ 8 and their interim study of Montana’s Public Retirement Systems on August 8th, 2021.

Over the last two decades, the Public Employees’ Retirement System (PERS) and the Teachers’ Retirement System (TRS) have experienced a fiscal transformation. In 2002, PERS was nearly fully funded with less than $1 million in unfunded pension benefits while TRS held $384 million in pension debt. Two decades later, both plans combined find themselves nearing $5 billion in earned, legally protected, yet unfunded retirement benefits that will inevitably need to be paid out to public workers.

Financial reporting from both systems clearly shows that the changing global investment landscape over the last 20 years has left Montana’s public pension systems struggling to catch up. Unfortunately, the State’s current approach to addressing both the cost of earned retirement benefits and financing unfunded liability payments to address growing pension debt is leading to compounding interest and significantly higher long-term costs.

Montana House Bill 323 (HB323) of the 2021 legislative session attempted to address the state’s growing unfunded public pension liability through improvements on contribution and amortization policies. This legislation was a novel way to enhance the solvency and resiliency of the state’s largest public pension systems that would have improved upon the state’s current practices.

ADEC Policy Would Codify Current Variable-Statutory Rate Practice

Every year, plan actuaries calculate the amount that needs to be contributed to the pension fund to keep it on track to achieve full funding within the established debt payment—or amortization—schedule. This figure is commonly called the actuarially determined employer contribution, or ADEC.

Montana’s current pension funding policy does not directly use ADEC to determine annual state contributions as a matter of law, but the policy does take the ADEC contribution rate into account as a moving target of sorts, requiring periodic adjustments.

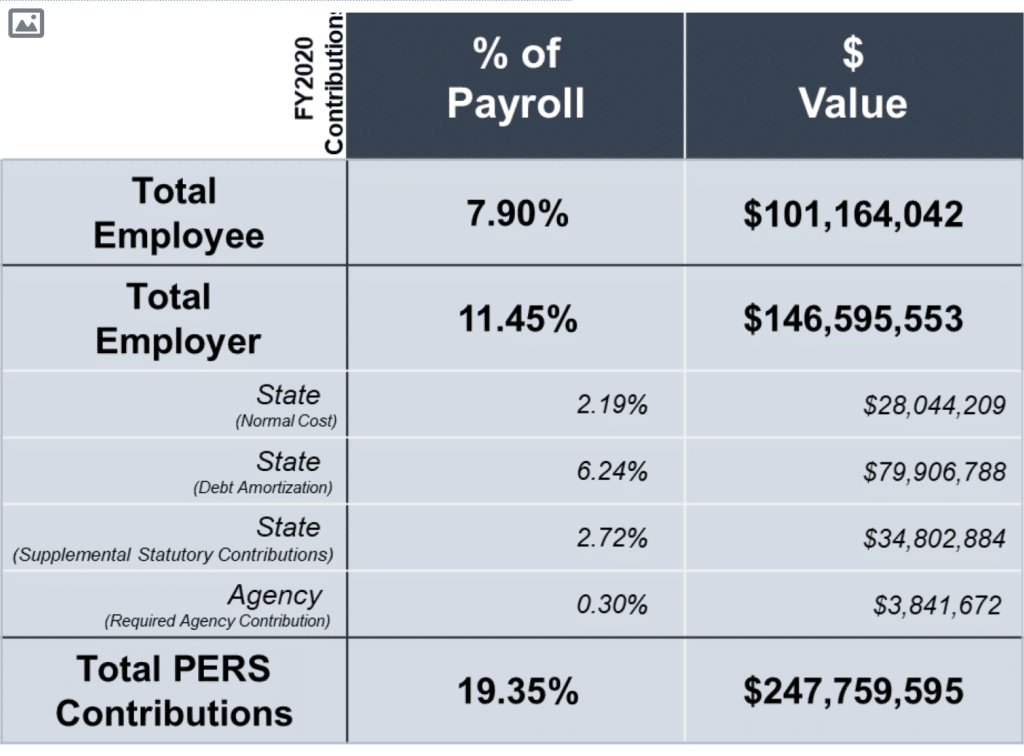

Table 1 – Make Up of PERS Contributions

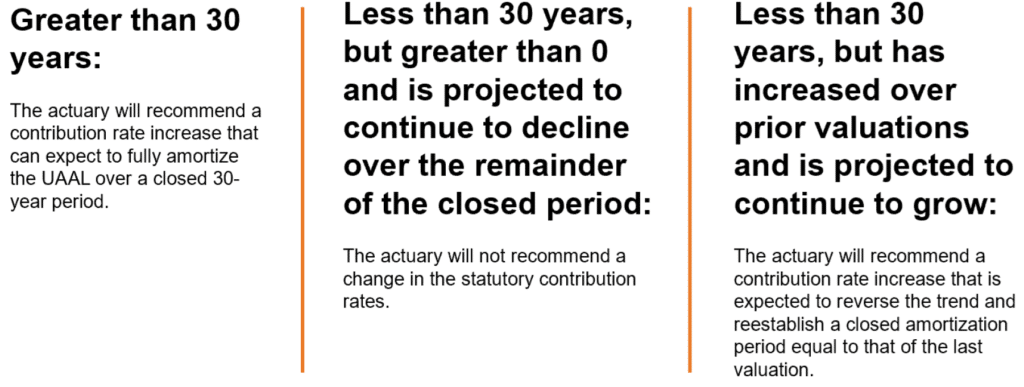

Rather than using ADEC to calculate the state’s contribution each year, the Montana legislature has long adjusted the state’s contribution rate in statute upon request by system actuaries. The employer contribution rate stays fixed in state law until the systems’ actuary expects the current contribution rate will not allow the plan to pay off its unfunded liabilities within a 30-year timeframe (see Figure 1). As a result of low investment returns, growing unfunded liabilities, and the state’s reflexive adjustments to funding needs, state contribution rates toward TRS and ERS have nearly tripled over the last two decades.

By relying on the system administrators’ requests and adjusting rates in statute in reaction to past experience instead of automatically amortizing unfunded liabilities as they occur with an ADEC rate, Montana’s public pension funding policy risks systematically underfunding earned and accrued—and constitutionally protected—retirement benefits.

Figure 1 – How Montana’s Current Variable-Statutory Employer Contribution Rate Adjust

If a pension system actuary calculates an amortization period:

Unfortunately, reacting to the poor actuarial or market performance by increasing contribution rates or lowering assumptions alone is often not a comprehensive way to address the causes of growing unfunded benefits. HB 323 would have committed the state to a set timetable for fully funding benefits instead of allowing the debt to perpetuate.

Switching to an ADEC Rate

Had it been enacted, the primary policy aspect of HB323 would have moved the state away from an employer contribution rate being set in statute—literally requiring an act of the legislature to change—to a rate that automatically adjusts every year to reflect the actuarially recommended ADEC amount.

For Montana PERS, negative deviations relative to current assumptions increase unfunded liabilities, often causing the funding period to exceed 30 years, requiring the legislature to periodically amend the statutorily fixed employer contribution rate. PERS actuaries also reset amortization payments to tackle the unfunded liability as part of their rate increase recommendation.

The highest level assessment of Montana’s current policy is that, absent any legal or policy requirement to use ADEC-based funding, the legislature and pension systems have demonstrated good stewardship over the years by trying to generally keep pace with ADEC rate levels over time. However, it appears your current policy is trying to “chase ADEC” instead of simply adopting a “set it and forget it,” true ADEC policy.

Stress Testing Montana’s Public Pension Systems

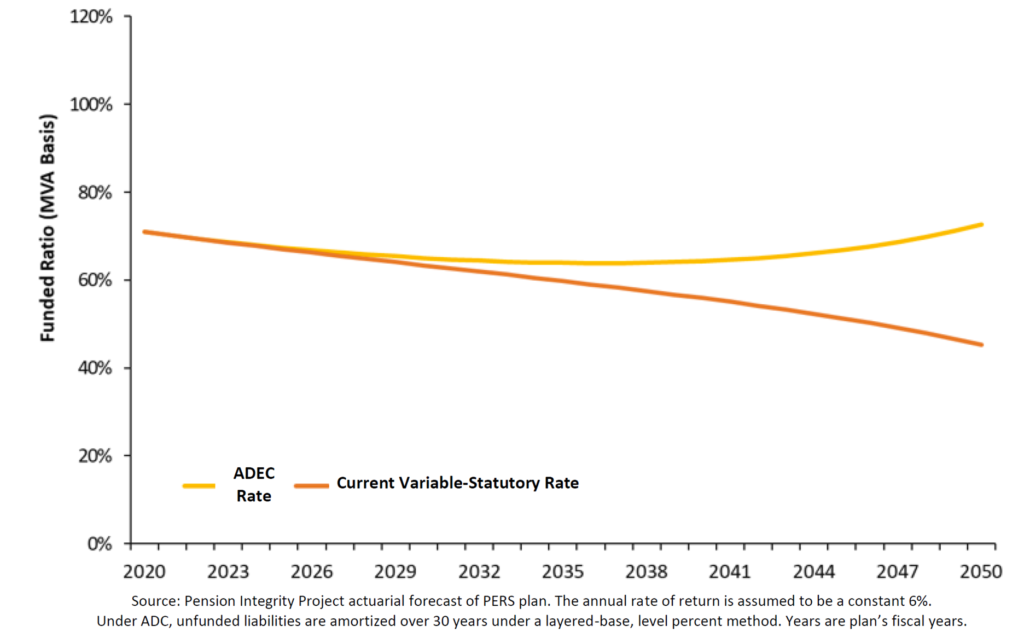

To understand the systemic challenges facing Montana’s pensions, it is valuable to examine the future of the plans under various stress scenarios. Reason’s forecast analysis of PERS shows that while the current contribution policy may keep the fund on track if investment returns match plan assumptions, it may prove insufficient if investments returns are lower or if the market is more volatile.

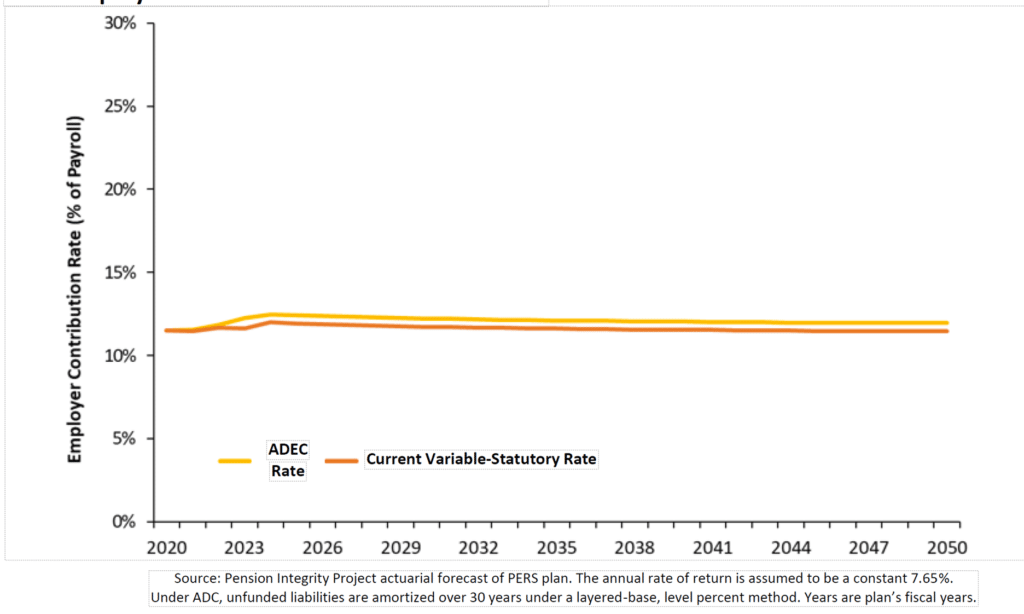

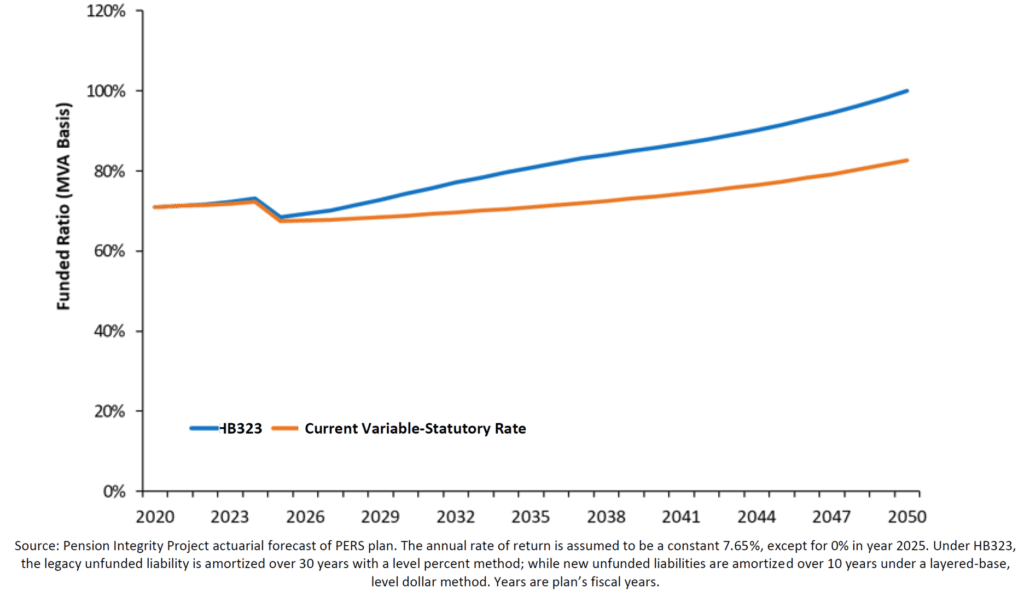

Figure 2 shows how the current 11.45% PERS employer contribution rate tracks closely with the ADEC rate under ideal investment return conditions. Figure 3 shows the projected funded status of PERS and reveals that both funding methods would help PERS achieve full funding by 2050 if the plan achieves its assumed rate of investment return.

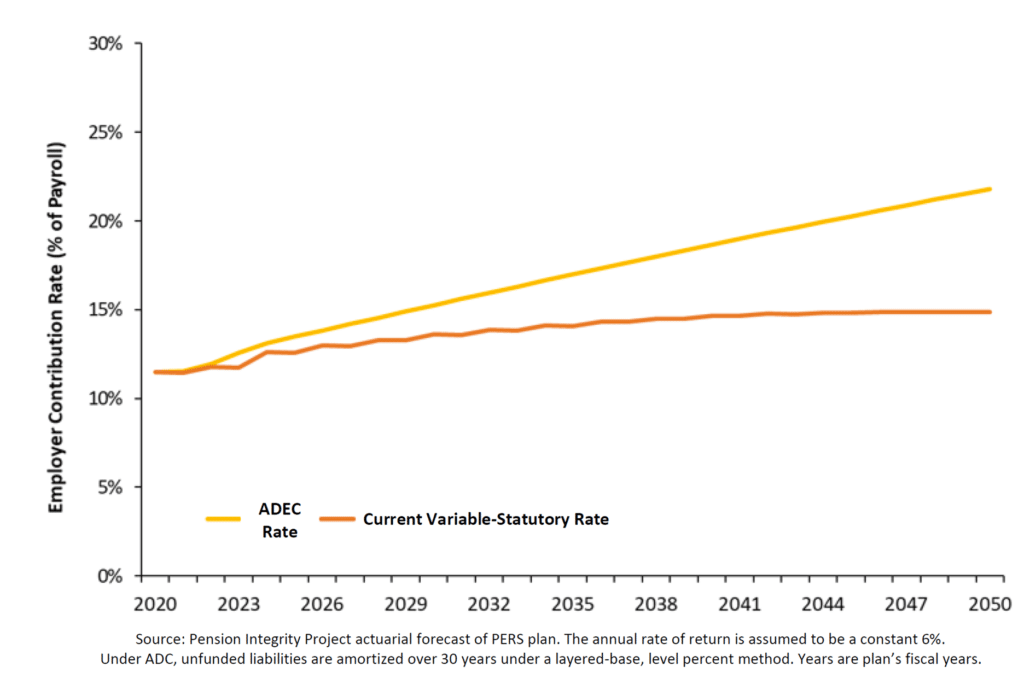

Although the funding policies deployed in both scenarios shown in Figures 2 and 3 look similar, they differ in their ability to react to market conditions. Given the propensity of Montana’s public pension systems to increase holdings in volatile assets to achieve high investment return assumptions, it is likely the plan will fall short of its investment return assumptions. Figure 4 shows an ADEC scenario with underperforming PERS investments that achieve only a 6% average rate of return versus the current 7.65% assumption.

Figure 2 – PERS Employer Contributions Under Ideal Returns

Figure 3 – PERS Funded Status Under Ideal Returns

Figure 4 – PERS Employer Contributions When Returns are Weak

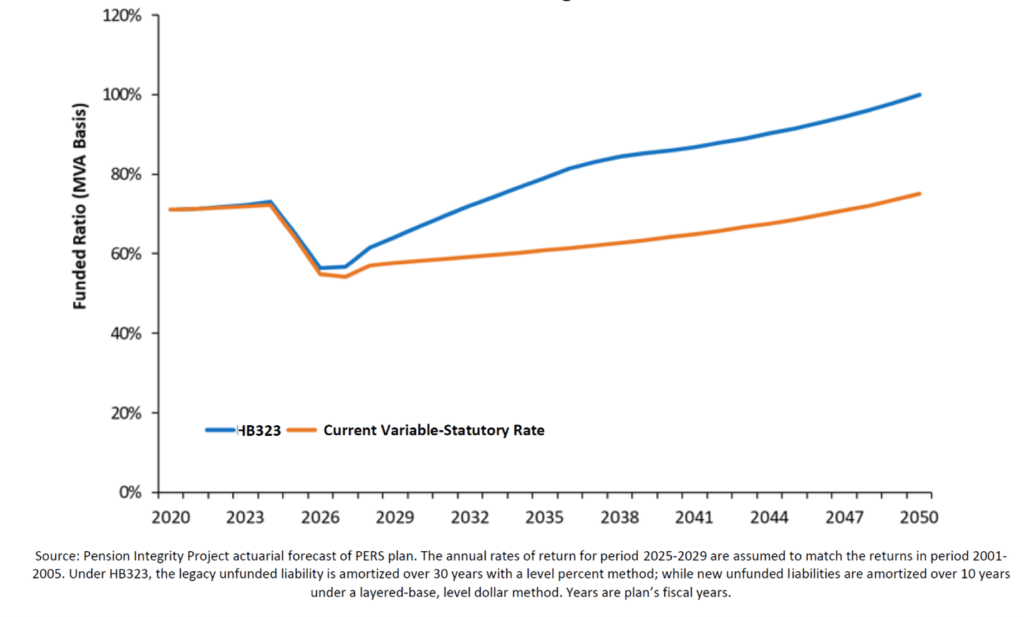

If the legislature continues the practice of maintaining a statutorily fixed rate, only increasing that rate after plan actuaries have identified a crisis, contribution rates are not expected to rise according to funding needs and the PERS funded ratio will likely decrease. Figure 5 shows that under Montana’s current practice, a 6% return would leave the plan at less than 50% funded in 2050.

The drop in funded status under weak investment conditions illustrates the need to adopt an ADEC policy, which would close the amortization period and eliminate current and future PERS unfunded liabilities in a relative 30 years (or whatever amortization window lawmakers choose) regardless of market performance.

Paying the ADEC rate makes contributions highly responsive to actuarial experience to make up for any shortfall (or surplus) over a predetermined time period. When comparing the state’s current PERS contribution practices to an ADEC policy, the current practice is more responsive than an entirely fixed statutory rate (a common, but poor practice in other states), but still less responsive than a true ADEC policy and less effective at fully addressing the unfunded liability within a set time period.

Figure 5 – PERS Funded Status When Returns are Weak

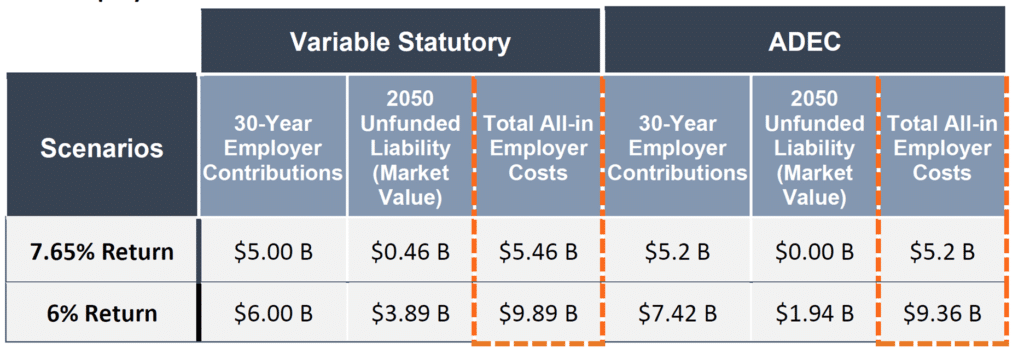

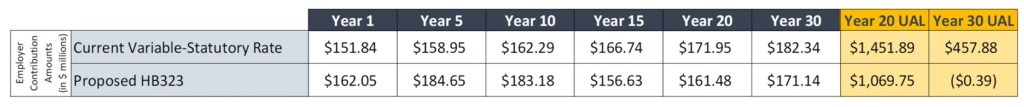

To give a clearer long-term perspective, the “All-in Employer Cost” combines 30-years of employer contributions with the ending unfunded liability. Such a perspective is important due to the legal protections afforded to earn pension benefits by the state constitution. The “All-in Employer Cost” calculation enables a clear comparison of the total long-term cost to government employers of one path relative to another.

The all-In cost in Table 2 illustrates the effect of adopting an ADEC policy, which closes the amortization period and eliminates current and future PERS unfunded liabilities in a relative 30 years if all assumptions prove accurate, saving taxpayers hundreds of millions. If plan investments underperform, an ADEC policy limits employer cost long-term in exchange for short-term appropriations. That major difference between how Montana funds public pension benefits today and the suggested funding policy under HB323 of 2021 is highlighted in Table 2 where PERS would be left with more unfunded benefits and the legislature with higher cost if the status quo is maintained.

Table 2 – PERS Employer All-In Cost

Addressing Current Unfunded Liabilities

The second major element of HB323 is how it would have adjusted the method by which the state and governmental employers address the current $5 billion in unfunded pension promises. Currently, unfunded retirement benefits are funded in a way that targets their full funding within 30 years.

As implemented however, the current policy has rates adjusting upward in response to actuarial experience not meeting expectations over a few years, leaving policymakers and employers with an unfunded liability that never truly reaches full funding.

Under HB323, all unfunded liabilities accrued before the measure is enacted would be set to amortize over the next 30 years, regardless of market performance, by assigning a clear due date and adjusting rates annually to meet that goal.

Addressing Future Unfunded Liabilities

Similar to paying the minimum on a large credit card bill each month, year after year, pension debt can continue to accrue through interest accrual despite contribution increases. In pension accounting, this concept is referred to as “negative amortization” which occurs when interest on pension debt exceeds annual amortization payments. Lowering the amount of time that debt is scheduled to be paid off reduces—and usually eliminates—negative amortization, better managing the cost to taxpayers and employers in the long-

term.

The final major element of HB323 is that it would have set all new unfunded liabilities to be amortized over 10 years, instead of the current 30-year target window, so any future unfunded liabilities are quickly amortized, greatly reducing the chances of perpetually growing pension debt.

PERS’ consulting actuary, Cavanaugh Macdonald, told the Legislative Finance Committee that a layered amortization policy like what is included in HB323 would be good for cash flow and an “actuary’s dream funding policy.” Layered amortization means all new UAL accrued in a given fiscal year is amortized over a short, fixed period such that each new year’s UAL is “layered” and paid down within the average service life of a typical public employee.

Exploring PERS Before and After HB323

Combining the three major elements of HB323 – adopting ADEC funding policy, addressing the current unfunded liability, and addressing future liabilities going forward – the following figures compare PERS in its current state to PERS under a scenario where HB323 is adopted.

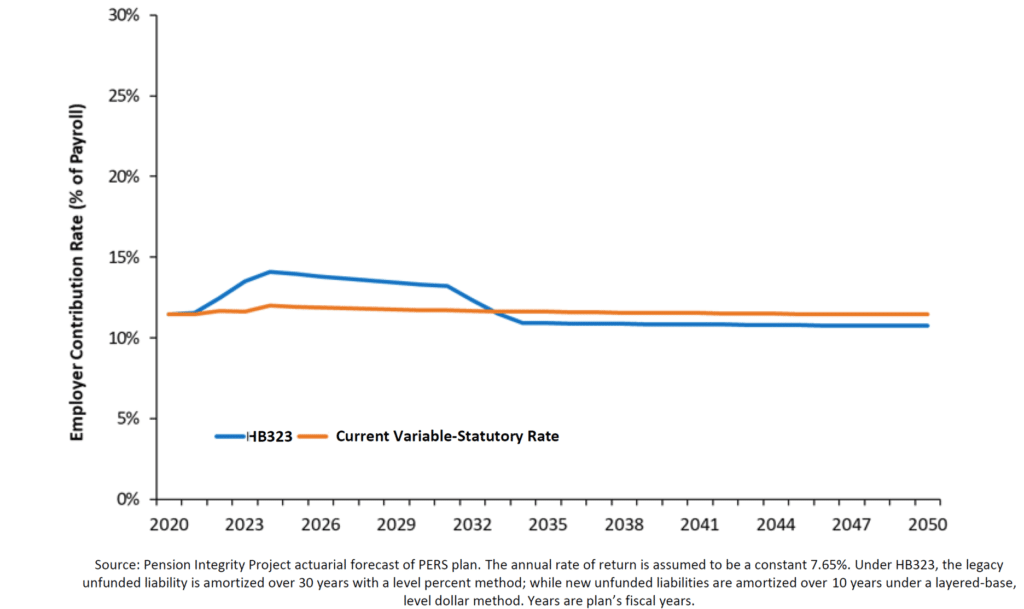

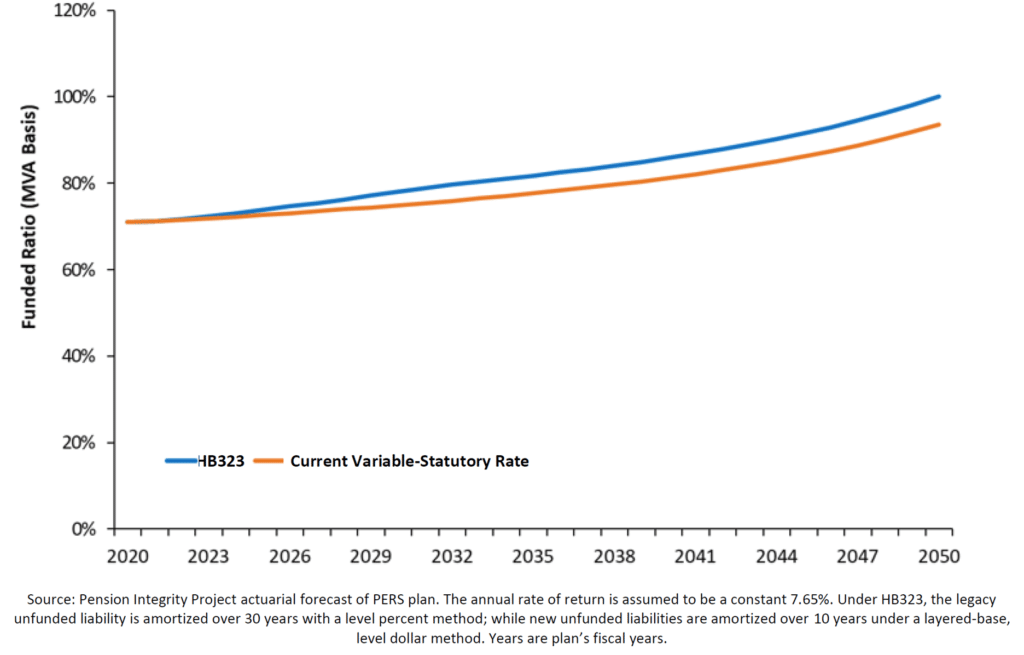

Assuming all investment and demographic assumptions prove accurate over the next 30 years, Figure 7 and Figure 8 compare PERS in its current state to PERS after the adoption of HB323.

Under the scenario in which actual returns match plan assumptions each year, HB323 would increase employer contributions over the next decade, but would also allow for a lower contribution after that. Additionally, the reform would slightly accelerate PERS’ path to full funding. Actual returns will not match plan assumptions year to year, however, and there is a good chance that long-term results will continue to land below the assumptions used. The true value of the proposed reform arises with a projection that does not meet the plan’s return assumptions.

Figure 7 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Employer Contributions Under Ideal Returns

Figure 8 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Funded Status Under Ideal Returns

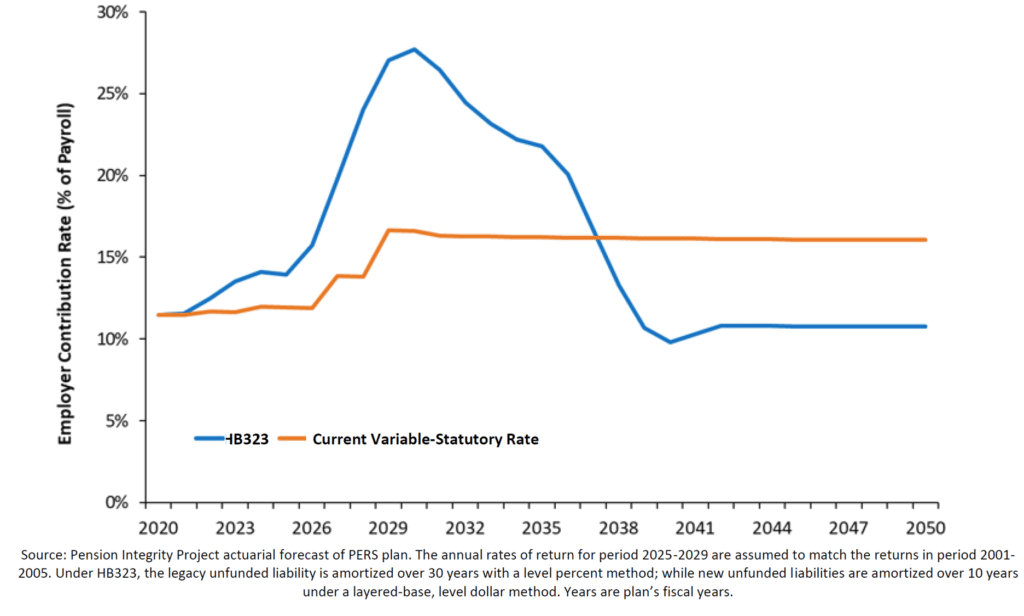

Figures 9 and 10 introduce market volatility into the actuarial equation. The results show how, although the current funding policy maintains a lower contribution level, millions of earned retirement benefits will go unfunded and continue to drive up cost long-term.

Figure 9 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Employer Contribution Rate Assuming One Year of 0% Returns

Figure 10 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Funded Status

Figures 11 and 12 use PERS’ own experience to show how the plan will respond to future recessions like the one following the Dot.com boom of the late 1990s. If PERS reacts to a future recession as it has in past recessions, the system would continue to accrue unfunded liabilities and lawmakers and employers will remain responsible for expensive amortization payments under the status quo funding policy.

Figure 11 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Employer Contribution Rate Assuming ’01–’05 Returns

Figure 12 – PERS Current State vs HB323 Funded Status Assuming ’01–‘05 Returns

Switching Montana’s pension funding policy from reactive to proactive by committing to contributions toward the state’s public pension systems at rates determined by plan actuaries leads to long-term savings as displayed in Table 3. Depending on actual market results, a funding policy like HB323 of 2021 would save the state as much as $1.58 billion over the observed 30 years.

Table 3 – PERS Employer All-In Cost

The actuarial analysis shows that Montana’s current approach to funding PERS is the most expensive path forward and the changes proposed in HB323 could generate significant savings. This effect is even more prominent if the system experiences economic volatility similar to the last two decades.

Fiscal Considerations

During the 2021 regular session, many budget-aware stakeholders and legislators expressed concerns over the potential contribution increases associated with the state adopting policies like those in HB323. Table 4 compares the status quo with the proposed funding policy included in HB323 of 2021 from an employer cost perspective. In exchange for prudent, navigable increases in the short-term, employers would not only expect a drop in required contribution about 15 years out but a complete elimination of all unfunded actuarially accrued liabilities

(UAL), which are earned retirement benefits for which sufficient funds have not been set aside.

Table 4 – PERS Employer Annual Contribution and Final Unfunded Liability

The rise in employer contributions required under HB323 can be mitigated to some degree with technical adjustments, but not avoided entirely regardless of if the solutions found in HB323 are adopted or not. The over $5 billion in earned retirement benefits currently unfunded will need to be funded somehow, and the bill will come due one day. HB323 accepts that reality facing PERS and TRS and commits to honoring the state’s obligation in the interest of future Montanans.

The moderate upfront fiscal impacts pale in comparison to the savings Montana would see from avoiding interest and eliminating pension debt amortization payments. Actuarial modeling shows that maintaining the status quo ensures Montana will continue to allow hundreds of millions in retirement benefits to go unfunded if left unchecked. The funding policy included in HB323 would have driven down long-term costs by eliminating all unfunded liabilities in 30 years if all assumptions proved accurate. But when assumptions are off, as they often are, the policy would have remained anchored to a full funding target, minimized costs and financial risks for taxpayers and protected retirement nest eggs. Retirement benefit contribution rate hikes for local employers and municipalities are best seen as inevitable no matter what, but under the current policy paying off the systems’ unfunded liabilities are not inevitable. A policy like HB323 would ensure those funds truly guarantee the elimination of Montana’s pension debt over the long run.

Conclusion

Shifting to a shorter, layered amortization schedule would lead to the faster payment of unfunded pension liabilities. Although shortening the amortization schedule can lead to a temporary increase in the employer contributions immediately, it saves the state and taxpayers more long-term, while providing a more stable pension plan for public employees and educators.

Paying off unfunded pension liabilities faster results in less interest accumulated, leading to lower total costs over the long run. Paying down pension debt quickly reduces the risk that down markets will generate perpetual growth in unfunded liabilities. The technical adjustments made to the state’s public pension funding policy included in HB323 of the 2021 regular session would have used contributions today to set Montana’s two largest pension systems on a course toward long-term solvency and cost reduction.

Stay in Touch with Our Pension Experts

Reason Foundation’s Pension Integrity Project has helped policymakers in states like Arizona, Colorado, Michigan, and Montana implement substantive pension reforms. Our monthly newsletter highlights the latest actuarial analysis and policy insights from our team.